Australian Marriage Celebrants (AMC)

To celebrate 50 Years of Civil Celebrancy held at the

NOVOTEL HOTEL, BRIGTON-LE-SANDS on Saturday, August 26, 2023 by Dally Messenger III

Opening Address Notes (not exactly as delivered!) to the gathering of civil marriage celebrants organised by Kamal Saliby, Annemarie McDonell, Leanne McKay and the committee of the AMC.

Good morning, fellow celebrants,

Thanks so much to Kamal Saliby, Annemarie McDonell, and Leanne McKay for inviting me to give this opening address, and for all they have done in organising this conference honouring our history.

So Garfield Barwick introduces the Marriage Act of 1961.

On a day such as today, it is necessary to record the key moments of our history. That wonderful axiom applies:

Let those who drink the water

remember those

who dug the well.

So we ask ourselves, How did it all happen?

So I will outline for you today some background, a picture of how it was at the beginning, and a few moments in the longer story from 1973 to 2023.

Before 1961, every state had its own Marriage Act. Garfield Barwick, the Liberal Party Attorney-General, and sometime later the Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia decided to combine all the state Marriage Acts into one federal Commonwealth law, the Marriage Act 1961. Its achievement was to apply consistent marriage law to the whole commonwealth.

I was 23 years old at the time, and I remember the media making this out to be an extraordinary achievement. I didn’t think so. But not many reforms went on in those days, so it was hailed. As an aside, you may be interested to know that in 1961, 14 year old girls and 16-year-old boys could be married with permission. It was not until 1991, when I was 53, that both parties had to be 18.

Senator Lionel Murphy enters parliament and campaigns for marriage law reform

In the same year, on April 30, an idealistic young lawyer in the Labor Party achieved preselection for the Senate by one vote. Nearly two years later (December 1962), he was elected Senator for NSW for the Australian Labor Party. (Hocking, pp. 69–70). His name was Lionel Murphy.

Though he was in opposition, he wanted to do all the good he could as a member of Parliament. So he made friends in the Liberal Party and fought for various causes in a bipartisan way, unthinkable today. He had an axiom he lived by.

If it adds to the sum total of human happiness,

You do it,

And if it doesn’t,

You don’t.

In 1967, he was elected leader of the opposition in the Senate. He put a great deal of his energy, alone, into reforming marriage law in Australia. He almost persuaded the Liberals to support him. He was determined and persistent. But he had a nasty opponent—Liberal Senator Ivor Greenwood.

In her captivating book on Murphy’s life, Dr. Jennifer Hocking recounts how Murphy, almost single-handedly, persisted for several years to achieve the groundbreaking reform of no-fault divorce. The implementation of the Family Law Act, which he eventually achieved when the Whitlam government was elected, brought about a revolutionary change, both legally and socially. After its enactment, it significantly diminished personal animosity within society. The cost of obtaining a divorce plummeted, in general terms, from an exorbitant $200,000 to a mere $400. However, this triumph did not come without an arduous and contentious struggle. Hocking declares:

No Act has provoked such controversy, traversed such a long and arduous parliamentary passage, or undergone such intense public scrutiny as Lionel Murphy’s Family Law Act.

Murphy’s achievement was all the more remarkable when one considers the dominance of religion at the time. The main Christian churches held sway, and visceral religious sectarianism, especially between Catholics and Anglicans, was a curse that plagued Australian society.

Dally Messenger becomes the first applicant to perform civil marriages.

But going back a bit I had studied this new Marriage Act of 1961 while I was in the seminary. Under Section 39, I applied for the authority to officiate at marriages to oblige a small group of friends who were horrified at the thought of a registry office marriage. Sir Garfield Barwick refused my application on the grounds that I was not affiliated with a religion. It was a different world from the one in which we live today. Religions were strong. Church attendance was high. Non-religious people, secular people, were the pits.

The Whitlam Labor government is elected to office

On December 2, 1972, the Whitlam Labor Government was elected to office. Murphy became Attorney General and leader of the Whitlam government in the Senate.

Attorney General Lionel Murphy achieves no-fault divorce

He was able to implement his radical reform measure—no fault divorce—the Family Law Act, for which he had worked so hard for so many years. It was enacted in 1975, but did not take effect until 1976, after Murphy had been appointed to the High Court in February 1975.

Attorney General Lionel Murphy appoints marriage celebrants, despite widespread opposition

But apart from reforming divorce laws, Murphy was angered by the way marriage ceremonies were conducted.

Allow me to describe the Sydney scene. The space was only open from Monday to Friday, between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. Within the room, the atmosphere was stark, austere, and disheartening. Couples who were ready to wed, along with their witnesses (only two allowed), were seated in an orderly manner on a long bench, waiting for their turn. A solemn official, with an expressionless face, called them up one by one from behind a desk. A dry and concise legal marriage ceremony followed. Once the ceremony was concluded, the group of four would be dismissed, making way for the next set of couples. At most, couples were permitted to take a single photo away from the desk.

Lionel Murphy, deeply dismayed by the unnecessary humiliation experienced by couples on what should have been a joyful and celebratory day. He took action. As Attorney-General, Murphy recognised an opportunity to restore dignity to secular individuals and divorced Christians in their marriage ceremonies. He utilised a simple provision in Garfield Barwick’s 1961 Marriage Act (Section 39) to empower ordinary citizens, unaffiliated with any specific religious group, to officiate at weddings. It was so simple for him, yet its effects were profound. These individuals quickly became known as civil marriage celebrants.

Despite opposition from every quarter—his colleagues in the Labor Party, the public service, and his own personal staff—Murphy, on July 19, 1973, appointed the first Civil Celebrant, Lois D’Arcy.

The true legend of the first appointment

The appointment of the first celebrant is the stuff of legend. On the fateful night of July 19, 1973, under the cover of darkness, Murphy personally typed out the appointment letter for the first celebrant, Lois D’Arcy, a vivacious young mother in her twenties hailing from Queensland. With determination, he then scoured his office until he located an envelope and stamp. After carefully addressing the envelope and moistening and affixing the stamp, he walked to a nearby post office box and firmly slid it into the slot. And thus, the civil celebrant program commenced.

Lois D’Arcy holds the esteemed distinction and honour of not only being the first truly independent civil celebrant appointed in Australia but, as fate would have it, in the entire Western world.

I was No. 17. When a public servant told him about my application to Barwick, he immediately called for my file. They couldn’t find it. He kept on insisting they had found it. Immediately, he sent me a telegram saying he had made me a celebrant. He told me all this himself.

Lionel Murphy’s enthusiastic interest in Civil Celebrant marriages

The program had a slow start. But then it started to roll on. Murphy took an enthusiastic interest in this program – sending telegrams of congratulations to the first several hundred couples married by civil celebrants. He would often unexpectedly turn up uninvited to weddings performed by celebrants, to mix with the couple and guests, and to delight in his achievement.

The radical reform of civil marriages

In the context of the time, appointing Mrs. D’Arcy was a truly radical reform. It was not just the power to “do” a wedding ceremony, It was the ideal to establish the kind of marriage ceremony that he felt would bring the most freedom and dignity to the ordinary person who was not a churchgoer. I interred him in the seventies; he used the word dignity 27 times.

His radical reform was that celebrants were to guide people in choosing their own ceremony, one that was most consistent with their values and ideals. The reader should understand the fierce criticism that was then in circulation regarding the words in church ceremonies that belittled women and non-believers.

Couples now had the freedom to choose their own celebrant, their own place, and their own time—liberties unheard of in the western world up to this point. He furthered the cause of women in our society by appointing mostly female celebrants. He appointed aboriginals. He appointed young people. He encouraged substance and beauty, in the components of the marriage ceremony, and later in funeral ceremonies.

Murphy appointed Messenger the first secretary of the organisation he founded.

On May 3, 1974, Murphy called upon every celebrant who could make it to his Sydney office to establish an association. Gathered before his desk, he addressed the twenty or so individuals present, expressing his conviction that the Whitlam government would inevitably lose the upcoming election. He was convinced that the Liberal Party would probably consider discontinuing the Civil Celebrant program to gain favour with the churches. In light of this, he announced that our most prudent course of action would be to unite by forming an association. He founded it there and then. The name became, and I made a contribution here, “The Association of Civil Marriage Celebrants of Australia,” the ACMCA.

In the aftermath, he made me the inaugural secretary of the association. His charge to me was clear: elevate the standards, dignify the ceremonies, and foster a collaborative sharing of resources. These concepts were novel to us at the time. Above all, his unwavering interest drove us forward. Navigating a fair share of media attention fell within my responsibilities as well.

Reflecting on those times, I’ve come to realise the profound positive impact he achieved in people’s lives through legal and human means. I felt great pride in being his “man on the ground.” His enthusiasm was infectious. As an aside, I have observed that government initiatives thrive only when a Minister remains engaged. Remarkably, in times of trouble, I could simply dial Canberra and be instantly connected to Murphy’s desk—an unimaginable convenience in today’s world.

During those years, our primary means of communication was by post, a labor-intensive process. Mobile phones, emails, Google, Wikipedia, Trove, and even chatGPT were nonexistent luxuries. Long-distance phone calls incurred exorbitant costs. It’s important to note that I was a volunteer.

Frequently, I would visit the office of the local Labor Member of Parliament for Dandenong, Max Oldmeadow, to mail letters and make those pricey long-distance calls. To this day, I extend my gratitude to the taxpayers. All my efforts were, ultimately, for your benefit.

Max was a gem, consistently aiding me in responding to celebrants across Australia. Lionel appointed 99 celebrants. We exchanged ceremonies, poems, ideas, and, yes, even mistakes. As there was no such thing as a portable PA system, we exchanged techniques for projecting our voices. A voice specialist celebrant, Jane Day, held classes on voice projection and clear diction. She quoted the preacher George Whitfield, whose projection and diction could be clearly heard by upwards of 10,000 people listening in the open.

The Gestetner machine ran ceaselessly as I sent out regular posts containing poems, ring wordings, vows, and valuable tips for organising, planning choreography, and placements.

As most weddings occurred in parks and gardens, we always needed a contingency plan for wind and rain. All this information reached the celebrants by way of informal discussion on our mailing list.

Speaking of choices, while it’s easy to proclaim that people can craft their own ceremonies, the reality, in the pre-internet era, was quite different. Consider this: Where did they draw inspiration from? Quality wedding poems that could be understood upon first reading were precious finds, not as abundant as you might believe. Eventually, we published a pamphlet, which evolved into a booklet, and then a rudimentary book.

Meetings of the ACMCA

We had meetings several times a year. Jill-Ellen Fuller was the President, Junie Morosi was Vice President and a prominent contributor. They both had strong ideas. At one stage, I was the only male on an eleven person committee. All very strong women.

The end of the honeymoon period: – Funeral Ceremonies

The honeymoon period lasted the best part of two years. It all came to a halt over the question of funeral ceremonies.

Out of the blue, I was asked to do a funeral ceremony. I told the young man whose wife had just died that we don’t do funeral ceremonies. I called Lionel Murphy at the High Court. Of course you must do them, he said—prepare them well and charge a proper fee. I came back to the Celebrants and told them about his reply. They all went ballistic. It was before the visit of Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, and so people did not talk about death.

Even though we had been doing a few weeks of funerals for awhile, it came to a head in the ACMCA. I was responding to the few celebrants who saw it my way. The executive and the Attorney General’s Department took the opposite stand. A testy debate, to put it mildly, ensued. I was accused of using my civil celebrant authorisation to exploit people in grief.

In a motion of no confidence, I was dismissed from the secretaryship and the committee of the ACMCA. A bitter division continued. Some years later the ACMCA broke up into state branches. I was persona non-grata, and I could not save it.

The President, Jill-Ellen Fuller put out a press release, to which the media responded. Marriage celebrants are only interested in happiness and life, not misery and death.

To finish my talk today. I just wish to mention four important periods in the subsequent history

1. The decade of the fixed fee. (see below)

2. The Pallotti conferences. (Information pending)

3. The period since September 1, 2003. The era of legal trivia (The press release of Daryl Williams) full explanation in preparation

4. What is Celebrancy all about? (The Ruddock experience – explanation in preparation

What ceremonies do. The good you do. In ceremonies, you can tell stories, express, transmit, and reinforce values, ideals, and ambitions. Ceremonies are there to give individuals a sense of identity, a sense of belonging, and a sense of self worth. They are there to recognise achievements, to witness commitments, to commemorate and retell history, to express appreciation, to assist people in adjusting to change, to trigger a healthy grief process, and much more.

My fellow celebrants, you are the ones who dive into people’s lives, inject a huge dose of happiness, and leave them with a lifelong happiness-bringing memory.

ENDS

****************************************************************

NOTE 1. The fixed fee and the destruction of standards.

In these early days, a fixed fee was established by regulations for conducting marriages. Initially, this fee was quite substantial, amounting to about 1/3 to half of the average wage, which in today’s terms would be equivalent to $600-$800. However, a shift occurred after Lionel’s involvement ceased, driven by some ill-conceived publicity from our president, who held the belief that the more money one earned, the more successful they appeared. Consequently, the media propagated the notion that Celebrants were amassing excessive wealth.

With inflation eroding the value of the fixed fee, a series of events unfolded. Quality standards began to decline. The appointment of new celebrants lacked proper guidance from seasoned mentors. While pioneer celebrants maintained their commitment to high standards, disinterested individuals who had become celebrants primarily for a quick financial gain started compromising our original ideals. This decline was evident in the deterioration of ceremony preparation, rehearsals, and related details. The public servants strictly enforced this lower fee structure, exacerbating the situation.

I recall an incident involving my former wife, Marj. She received a letter from the department, inquiring whether she had received a bottle of champagne in addition to the prescribed fee. Someone had reported her for it. The effort invested in assisting couples no longer seemed justified by the monetary compensation.

Subsequent to this point in history, there have been numerous fluctuations marked by both successes and setbacks. To delve into the detailed trajectory, one would need to consult the historical accounts provided in the book.

NOTE 2. Just as an addendum, I have donated 14 boxes of my personal records to the State library of Victoria.

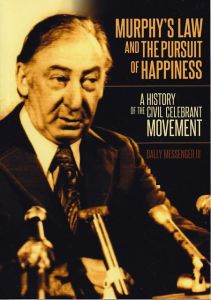

NOTE 3. My book – Murphy’s Law and the Pursuit of Happiness: A History of the Civil Celebrant Movement is available from the Celebrants Centre, Yvonne Werner, 0411 128 285 weare@celebrantcentre.com.au .

Max was a gem, consistently aiding me in responding to celebrants across Australia. Lionel appointed 99 celebrants. We exchanged ceremonies, poems, ideas, and, yes, even mistakes. As there was no such thing as a portable PA system, we exchanged techniques for projecting our voices. A voice specialist celebrant, Jane Day, held classes on voice projection and clear diction. She quoted the preacher George Whitfield, whose projection and diction could be clearly heard by upwards of 10,000 people listening in the open.

The Gestetner machine ran ceaselessly as I sent out regular posts containing poems, ring wordings, vows, and valuable tips for organising, planning choreography, and placements.

As most weddings occurred in parks and gardens, we always needed a contingency plan for wind and rain. All this information reached the celebrants by way of informal discussion on our mailing list.

Speaking of choices, while it’s easy to proclaim that people can craft their own ceremonies, the reality, in the pre-internet era, was quite different. Consider this: Where did they draw inspiration from? Quality wedding poems that could be understood upon first reading were precious finds, not as abundant as you might believe. Eventually, we published a pamphlet, which evolved into a booklet, and then a rudimentary book.

Meetings of the ACMCA

We had meetings several times a year. Jill-Ellen Fuller was the President, Junie Morosi was Vice President and a prominent contributor. They both had strong ideas. At one stage, I was the only male on an eleven person committee. All very strong women.

The end of the honeymoon period: – Funeral Ceremonies

The honeymoon period lasted the best part of two years. It all came to a halt over the question of funeral ceremonies.

Out of the blue, I was asked to do a funeral ceremony. I told the young man whose wife had just died that we don’t do funeral ceremonies. I called Lionel Murphy at the High Court. Of course you must do them, he said—prepare them well and charge a proper fee. I came back to the Celebrants and told them about his reply. They all went ballistic. It was before the visit of Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, and so people did not talk about death.

Even though we had been doing a few weeks of funerals for awhile, it came to a head in the ACMCA. I was responding to the few celebrants who saw it my way. The executive and the Attorney General’s Department took the opposite stand. A testy debate, to put it mildly, ensued. I was accused of using my civil celebrant authorisation to exploit people in grief.

In a motion of no confidence, I was dismissed from the secretaryship and the committee of the ACMCA. A bitter division continued. Some years later the ACMCA broke up into state branches. I was persona non-grata, and I could not save it.

The President, Jill-Ellen Fuller put out a press release, to which the media responded. Marriage celebrants are only interested in happiness and life, not misery and death.

To finish my talk today. I just wish to mention four important periods in the subsequent history

1. The decade of the fixed fee. (see below)

2. The Pallotti conferences. (Information pending)

3. The period since September 1, 2003. The era of legal trivia (The press release of Daryl Williams) full explanation in preparation

4. What is Celebrancy all about? (The Ruddock experience – explanation in preparation

What ceremonies do. The good you do. In ceremonies, you can tell stories, express, transmit, and reinforce values, ideals, and ambitions. Ceremonies are there to give individuals a sense of identity, a sense of belonging, and a sense of self worth. They are there to recognise achievements, to witness commitments, to commemorate and retell history, to express appreciation, to assist people in adjusting to change, to trigger a healthy grief process, and much more.

My fellow celebrants, you are the ones who dive into people’s lives, inject a huge dose of happiness, and leave them with a lifelong happiness-bringing memory.

ENDS

****************************************************************

NOTE 1. The fixed fee and the destruction of standards.

In these early days, a fixed fee was established by regulations for conducting marriages. Initially, this fee was quite substantial, amounting to about 1/3 to half of the average wage, which in today’s terms would be equivalent to $600-$800. However, a shift occurred after Lionel’s involvement ceased, driven by some ill-conceived publicity from our president, who held the belief that the more money one earned, the more successful they appeared. Consequently, the media propagated the notion that Celebrants were amassing excessive wealth.

With inflation eroding the value of the fixed fee, a series of events unfolded. Quality standards began to decline. The appointment of new celebrants lacked proper guidance from seasoned mentors. While pioneer celebrants maintained their commitment to high standards, disinterested individuals who had become celebrants primarily for a quick financial gain started compromising our original ideals. This decline was evident in the deterioration of ceremony preparation, rehearsals, and related details. The public servants strictly enforced this lower fee structure, exacerbating the situation.

I recall an incident involving my former wife, Marj. She received a letter from the department, inquiring whether she had received a bottle of champagne in addition to the prescribed fee. Someone had reported her for it. The effort invested in assisting couples no longer seemed justified by the monetary compensation.

Subsequent to this point in history, there have been numerous fluctuations marked by both successes and setbacks. To delve into the detailed trajectory, one would need to consult the historical accounts provided in the book.

NOTE 2. Just as an addendum, I have donated 14 boxes of my personal records to the State library of Victoria.

NOTE 3. My book – Murphy’s Law and the Pursuit of Happiness: A History of the Civil Celebrant Movement is available from the Celebrants Centre, Yvonne Werner, 0411 128 285 weare@celebrantcentre.com.au .